It’s cool outside and it’s slowly getting dark as we arrive at Olga’s office on a Friday afternoon. It is located at the end of a long corridor, the door looks very robust, with many locks and bolts. No wonder: we are still in the heart of the Colombian capital Bogotá, a city where there aremany problems today.

I bent over backwards to meet Olga, but the long journey was worth it, because the meeting with her proves to be a stroke of luck: She speaks German and has lived in Hassia for many years. The patient, interested and open Colombian is happy to tell us her story.

After living in Germany for years she moved back to Colombia and wanted to do something forthe people here – a meaningful job to support her fellow countrymenSo she started to export fairly produced jewellery to Europe. But that wasn’t that easy, because her export company “La Cucaracha” doesn’t have a Fairtrade certificate yet. There are very few companies in the Colombian crafts sector that possess such a certificate. This is mainly due to the high costs involved, which the manufacturer, not the importer, has to bear.

It is a paradox, I can’t help thinking, in a country like Colombia, with low wages and profits, when the companies not only have to be pay for the certification from Europe, but also the flights and hosting the certifier. For only a few companies is the certificate is paid by the importer, for example “Miquelina”, a company that produces outdoor clothing (find an articel of my visit at their factory here: https://fairtradeajourney.org/en/2019/04/30/it-all-started-with-a-nuns-project/).

Unfortunately, Colombia is generally less attractive as a production country than many Asian countries, as wages and goods are relatively “high” here.

In Europe, however, we actually want to use fair trade to ensure that people in the producing countries earn more. Instead, the companies first have to invest money they probably don’t even have. And the seal does not give them a guarantee of purchase, so they bear the full risk. “Is there no governmental agency in Colombia that supports you entrepreneurs? “Yes”, says Olga, “The WFTO[1] (World Fairtrade Organisation, the international umbrella organisation for fair trade organisations) has a Latin American office in Paraguay. And then there is ProColombia, which has offices in various countries around the world, including Frankfurt in Germany. ProColombia contacts potential importers, invites them to Colombia, also organizes trade fairs for craftsmen. That’s how EZA[2] (Austria’s largest Fairtrade import organisation) also became aware of “La Cucaracha”. An EZA person then carries out an audit and re-audits every 2 years to ensure that the minimum standards of fair trade are complied to. For example, the products are produced free of child labour and the workers receive a wage that at least corresponds to the govermental minimum wage in the respective country. In Colombia, this is currently 828,116 Colombian pesos , which corresponds to about €235 or roundabout $265 USD. In addition there is a transport cost subsidy, for example, a bus ticket of not quite 100,000 Pesos (about €26 or $30 USD). Per month! That seems not enough. Colombia is cheap, for us Europeans at least. One can have a lunch menu already for 2 or 3 € (2.2-3.3 $ US) , but imported goods as for example Niveacreme, cost almost as much as here in Germany. Thus, one cannot make big leaps with the minimum wage and I highly doubt, that it can be enough for a good life. So if Fairtrade only guarantees compliance with the minimum wage, does that mean, there are people who have to survive with even less? Apparently yes. Because: “In the countryside”, Olga tells me, “it is often even less because the employers often do not comply with the minimum wage requirements”.

I keep forgetting that German standards do not apply here and am very grateful to have grown up in a country with such a good economic situation and a stable social system. However, it makes it all the more important that people who manufacture products for me are at least not exploited. This should be the case with fair trade, because in addition to the minimum wage it also guarantees that the legal working hours are not exceeded and that the workplace is designed safely so that no health hazards such as poisoning by chemicals or injuries from unsafe machines etc. can occur.

In summary, the higher price we pay in Western countries for Fairtrade products is intended to allow the people who produce our jewellery, our outdoor clothing or our coffee live a better life. In other words, when we buy any product, we always vote on the manufacturing conditions as well. Of course, this is not only the duty of the consumer, but they do have the opportunity to express their opinions on the conditions of production by their decision of what to buy. Even if not everyone can always afford the usually somewhat more expensive Fairtrade products, often less is more when it comes to consumption.

So in the end the Fairtrade seal guarantees a slightly higher wage, but direct imports often lead to even better conditions for the workers. Olga, for example, pays twice the minimum wage and is guided by the so called „Living Wage“[3]. The Living Wage is the minimum income a worker needs to meet his basic needs. This includes food, shelter and other basic needs such as clothing. The Living Wage aims to provide workers with a basic but decent standard of living. I think this is good, because this is how I imagine fair trade: that the manufacturers can make a decent living from their work.

And how is Olga doing at the moment?

At the moment “La Cucaracha” exports about 1,000 pieces per month. Twice a year there is a new design that Olga develops herself: among other things, she creates beautiful, light pieces of jewellery made of silk cocoons. Olga also tells me why silk is an important product here. It was introduced to Colombia in the 1980s, because to grow silkworms you need about the same climate as for coffee. However, coffee is a slow-growing product. After planting the trees, it takes 18 months until the red cherry can be harvested for the first time (to learn more about coffee cultivation please click here). After the first harvest, the coffee also only ripens every 6 months. In the meantime, the coffee farmer has no income, but time for other things, such as silk production.

In Olga’s office I also see light earrings made of pumpkin skin, cleverly carved and beautifully painted. “The pumpkin grows deep in the south of Colombia, but is processed here. This is the only way I can control production and production conditions.”

Olga is obviously proud of what she has built up here with much effort and heart and soul – and rightly so. “But of course we would be happy if we could export even more products to Europe” she says and smiles at me. “At the moment it is only a sideline for all producers, the orders are not enough to make a living. Besides, I am not yet certified, which makes exporting more difficult. The audit has already taken place and I have also been re-audited, but I simply cannot afford the seal. At the moment I’m looking for a sponsor and hope to get the money for the Fairtrade certificate.”

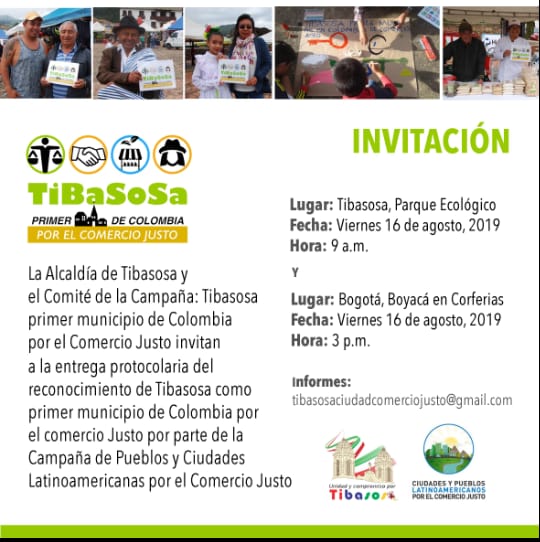

So the idea of Fairtrade is undoubtedly a good one, but since the seals represent a major financial investment for the exporter or manufacturer, which many small companies cannot afford at all, I cannot avoid finding the system somewhat centered of the „wests“ needs. It is less based on the realities of the people in the producing countries than on our system and our ideas of how business, trade, partnership and certification should work. Olga laughs. Yes, she agrees. And to prove how strong the dominance of the importing countries is also in this form of trade, she tells me the story of Tibasosa, 250 km away from here. Tibasosa a progressive community in which the first female mayor of Colombia was elected in 1963 (and thus only 15 years after the first German female mayor Erika Keck in Ahrensburg). This city wanted to become the first Fairtrade city of Colombia. As is my hometown Darmstadt since 2013 or Trier, with its own fair city coffee (to learn more about the Trier fair trade city coffee click here) since 2010, as well as 594 cities in Germany and 2.174 Fairtrade Towns worldwide.

Already if you look at the map of http://www.fairtradetowns.org/, one thing is very obvious: Most of the Fairtrade towns are in western countries; Great Britain and Germany alone make up more than half. That certainly speaks for these two countries. At the same time, it seems odd that the 635 cities in Great Britain are only facing 7 cities throughout Latin America, none of them in Colombia.

So far, Tibasosa could not become a Fairtrade city because there were no Fairtrade certified growers near the village who wanted to participate. The community is also not quite commited. But that might change soon, because in May 2019 the international Fairtrade Day was celebrated there. On this day there was a market with many farmers from the region. Some of them are already Fairtrade certified. Soon the dream could come true: The mayor has promised a budget and during this year a Fairtrade Town representative sould visit. With a lot of commitment and a bit of luck, Tibasosa could become Colombia’s first Fairtrade city – we keep our fingers crossed

Edit September 2019: Recently Olga sent me this picture. An invitation from Tibasosa which celebrates that it is Colombia’s first fairtrade town – a great success!

[1] https://wfto.com/

[2] https://www.eza.cc/eza-english

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Living_wage